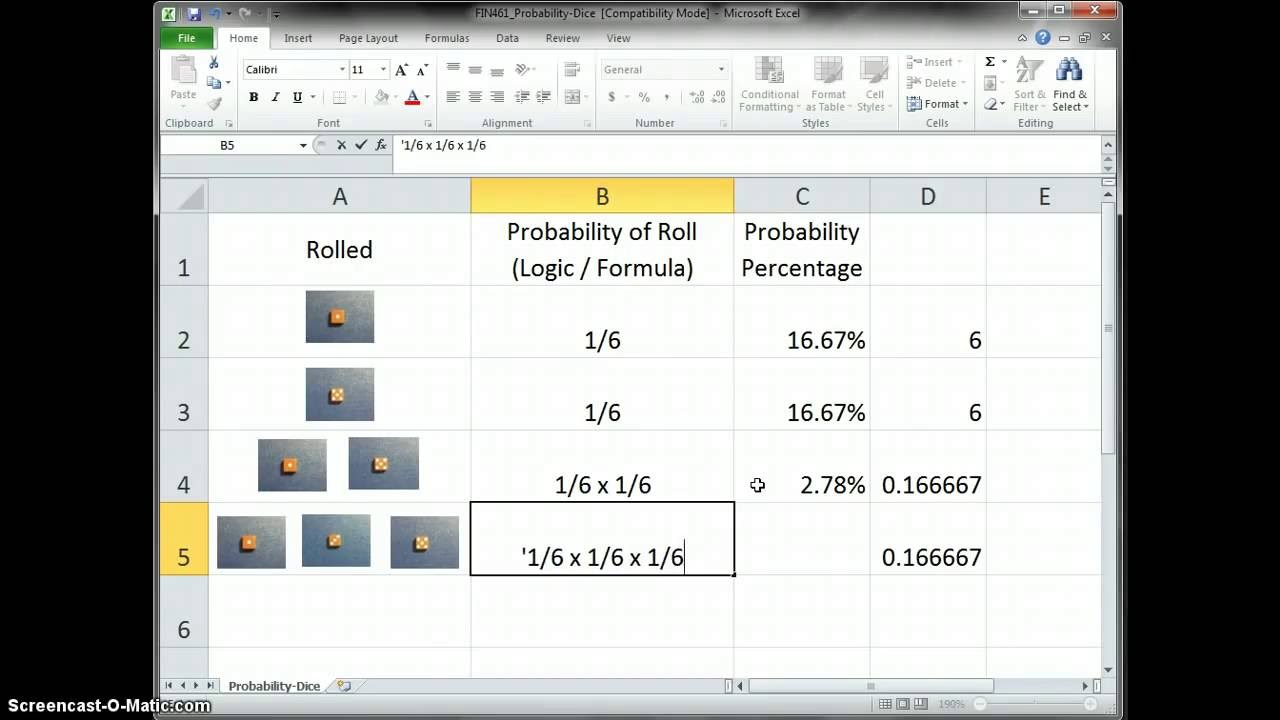

One popular way to study probability is to roll dice. A standard die has six sides printed with little dots numbering 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. If the die is fair (and we will assume that all of them are), then each of these outcomes is equally likely. Since there are six possible outcomes, the probability of obtaining any side of the die is 1/6. The dice probability calculator is a great tool if you want to estimate the dice roll probability over numerous variants. There are may different polyhedral die included, so you can explore the probability of a 20 sided die as well as that of a regular cubic die. On each roll, the probability of total 5 is $4/36$, and the probability of total 7 is $6/36$. Notice that if Nancy rolls any total other than 5 or 7, her situation has not changed at all: she still needs to keep rolling until the dice show 5 or 7, and will get the same results.

Alter then so that one die has a six on every side, and the other one has all ones and fives.

Thanks for the kind words. No, I don't think that wishful thinking helps in the casino, all other things being equal.

The question on the dice influence is a hotly debated topic. Personally, I'm very skeptical. As I review this reply in 2013 I still have yet to see convincing evidence anybody can influence enough to have an advantage.

I'm very skeptical of it. I go over some of the experiments on the topic in my craps appendix 3.

I don’t believe in it. So far I have yet to see a name I respect endorse the method, nor any evidence that it works. While I don’t entirely rule out the possibility I am extremely skeptical of it. I may live in Nevada but when it comes to things like dice setting I’m from Missouri, 'show me' it works.

With ordinary dice, the like those you get in a board game, this is true. However casino dice have inlaid spots. At the factory they drill holes for the spots then insert white colored spots into the holes, of the same density as the die itself. So the die is essentially a perfect cube. Even if they did use ordinary dice from a board game I doubt the bias would be nearly enough to overcome the house edge.

I think there is no such thing as a naturally bad shooter. With the possible exception of a few pros all dice throws can be considered truly random. There are seminars on how to overcome the house edge in craps by precession throwing but I make no claims for or against them. I have yet to see enough evidence either way.

I lost the $1800 to another gambling writer, not Stanford. I would have preferred more rolls but there was an obvious time contraint. Assuming one throw per minute it would take 34.7 days to throw the dice 50,000 times. I wasn’t the one who decided on 500 but it seemed like a reasonable compromise between a large sample size and time. You are right that 500 is too few to make a good case for or against influencing the dice, but 500 throws is better than zero.

For large numbers of throws we can use the Gaussian Curve approximation. The expected number of sevens in 655 throws is 655 × (1/6) = 109.1667. The variance is 655 × (1/6) × (5/6) = 90.9722. The standard deviation is sqr(90.9722) = 9.5379. Your 78 sevens is 109.1667 − 78 = 31.1667 less than expectation. This is (31.1667 - 0.5)/9.5379 = 3.22 standard deviations below expectation. The probability of falling 3.22 or more standard deviations south of expectations is 0.000641, or 1 in 1,560. I got this figure in Excel, using the formula, normsdist(-3.22).

This is about controlling the dice at Craps. You previously discussed the Stanford Wong Experiment, stating, 'The terms of the bet were whether precision shooters could roll fewer than 79.5 sevens in 500 rolls of the dice. The expected number in a random game would be 83.33. The probability of rolling 79 or fewer sevens in 500 random rolls is 32.66%.... The probability of rolling 74 or fewer sevens in 500 random rolls is 14.41%.'The question I have about this bet is that 14.41% still isn’t 'statistically significant' [ i.e. p < 0.05 ] , which is usually taken to mean greater than two Standard Deviations from the Mean -- or a probability of less than a *combined* 5% of the event happening randomly on EITHER end of the series.

How many Sevens would have to be rolled in 500 rolls before you could say that there is a less than 2.5% chance that the outcome was entirely random (i.e. that the outcome was statistically significant) ?

Many Thanks & BTW , yours is ABSOLUTELY the BEST web site on the subject of gambling odds & probabilities that I’ve found .... keep up the good work !!!

Thank you for the kind words. You should not state the probability that the throws were non-random is p. The way it should be phrased is the probability that a random game would produce such a result is p. Nobody expected 500 rolls to prove or disprove anything. It wasn’t I who set the line at 79.5 sevens, but I doubt it was chosen to be statistically significant; but rather, I suspect the it was a point at which both parties would agree to the bet.

The 2.5% level of significance is 1.96 standard deviations from expectations. This can be found with the formula =normsinv(0.025) in Excel. The standard deviation of 500 rolls is sqr(500*(1/6)*(5/6)) = 8.333. So 1.96 standard deviations is 1.96 * 8.333 = 16.333 rolls south of expectations. The expected number of sevens in 500 throws is 500*(1/6) = 83.333. So 1.96 standard deviations south of that is 83.333 − 16.333 = 67. Checking this using the binomial distribution, the exact probability of 67 or fewer sevens is 2.627%.

There is no definitive point at which confidence is earned. It is a matter of degree. First, I would ask what is being tested for, and what the shooter estimates will happen. With any test there are two possible errors. A skilled shooter might fail, because of bad luck, or a random shooter might pass because of good luck. Of the two, I would prefer to avoid a false positive. I think a reasonable test would set the probability of a false negative at about 5%, and a false positive at about 1%.

For example, suppose the claimant says he can average one total of seven every seven throws of the dice. A random shooter would throw one seven every six throws, on average. By trial and error I find that a test meeting both these criteria would be to throw the dice 3,600 times, and require 547 or fewer sevens to pass, or one seven per 6.58 rolls.

A one in seven shooter should average 514.3 sevens, with a standard deviation of 21.00. Using the Gaussian approximation, the probability of such a skilled shooter throwing 548 or more sevens (a false negative) is 5.7%. A random shooter should average 600 sevens, with a standard deviation of 22.36. The probability of a random shooter passing the test (a false positive) is 0.94%. The graph below shows the possibe results for skilled and random shooters. If the results are to the left of the green line, then I would consider the shooter to have passed the test, and I would bet on him.

The practical dilemma is if we assume two throws per minute, it would take 30 hours to conduct the test. Perhaps I could be more liberal about the significance level, to cut down the time requirement, but the results would not be as convincing. I do think the time has come for a bigger test than the 500-roll Wong experiment.

First of all, she rolled the dice a total of 154 times, with the 154th roll being a seven out (Source: NJ.com). However, that does not mean she never rolled a seven in the first 153 rolls. She could have rolled lots of them on come out rolls. As I show in my May 3, 2003 column, the probability of making it to the 154th roll is 1 in 5.6 billion. The odds of winning Mega Millions are 1 in combin(56,5)*46 = 175,711,536. So going 154 rolls or more is about 32 times as hard. Given enough time and tables, which I think exist, something like this was bound to happen sooner or later. So, I wouldn't suspect cheating. I roughly estimate the probability that this happens any given year to be about 1%.

Also see my solution, expressed in matrices, at mathproblems.info, problem 204.

I think some of the casinos in Las Vegas are using dice that are weighted on one side. As evidence, I submit the results of 244 throws I collected at a Strip casino. What are the odds results this skewed could come from fair dice?| Dice Test Data | |

| Dice Total | Observations |

| 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 12 |

| 4 | 14 |

| 5 | 18 |

| 6 | 23 |

| 7 | 50 |

| 8 | 36 |

| 9 | 37 |

| 10 | 27 |

| 11 | 14 |

| 12 | 7 |

| Total | 244 |

7.7%.

The chi-squared test is perfectly suited to this kind of question. To use the test, take (a-e)2/e for each category, where a is the actual outcome, and e is the expected outcome. For example, the expected number of rolls totaling 2 in 244 throws is 244×(1/36) = 6.777778. If you don’t understand why the probability of rolling a 2 is 1/36, then please read my page on dice probability basics. For the chi-squared value for a total of 2, a=6 and e=6.777778, so (a-e)2/e = (6-6.777778)2/6.777778 = 0.089253802.

Chi-Squared Results

| Dice Total | Observations | Expected | Chi-Squared |

| 2 | 6 | 6.777778 | 0.089253 |

| 3 | 12 | 13.555556 | 0.178506 |

| 4 | 14 | 20.333333 | 1.972678 |

| 5 | 18 | 27.111111 | 3.061931 |

| 6 | 23 | 33.888889 | 3.498725 |

| 7 | 50 | 40.666667 | 2.142077 |

| 8 | 36 | 33.888889 | 0.131512 |

| 9 | 37 | 27.111111 | 3.607013 |

| 10 | 27 | 20.333333 | 2.185792 |

| 11 | 14 | 13.555556 | 0.014572 |

| 12 | 7 | 6.777778 | 0.007286 |

| Total | 244 | 244 | 16.889344 |

Then take the sum of the chi-squared column. In this example, the sum is 16.889344. That is called the chi-squared statistic. The number of 'degrees of freedom' is one less than the number of categories in the data, in this case 11-1=10. Finally, either look up a chi-squared statistic of 10.52 and 10 degrees of freedom in a statistics table, or use the formula =chidist(16.889344,10) in Excel. Either will give you a result of 7.7%. That means that the probability fair dice would produce results this skewed or more is 7.7%. The bottom line is while these results are more skewed than would be expected, they are not skewed enough to raise any eyebrows. If you continue this test, I would suggest collecting the individual outcome of each die, rather than the sum. It should also be noted that the chi-squared test is not appropriate if the expected number of outcomes of a category is low. A minimum expectation of 5 is a figure commonly bandied about.

Craps Dice Roll Probability

Whether or not it is called a valid roll depends on where you are. New Jersey gaming regulation 19:47-1.9(a) states:

A roll of the dice shall be invalid whenever either or both of the dice go off the table or whenever one die comes to rest on top of the other. -- NJ 19:47-1.9(a)

Pennsylvania has the exact same regulation, Section 537.9(a):

A roll of the dice shall be invalid whenever either or both of the dice go off the table or whenever one die comes to rest on top of the other. -- PA 537.9(a)

I asked a Las Vegas dice dealer who said that here it would be called a valid roll, if it was otherwise a proper throw. Although he has never seen it happen, he said if it did the dealers would simply move the top die to see what number the lower die landed on. However, one can determine the outcome of the lower die without touching, or looking through, the top die. Here is how to do it. First, by looking at the four sides you can narrow down the possibilities on top to two. Here is how to tell according to the three possibilities.

- 1 or 6: Look for the 3. If the high dot is bordering the 5, the 1 is on top. Otherwise, if it is bordering the the 2, the 6 is on top.

- 2 or 5: Look for the 3. If the high dot is bordering the 6, the 2 is on top. Otherwise, if it is bordering the the 1, the 5 is on top.

- 3 or 4: Look for the 2. If the high dot is bordering the 6, the 3 is on top. Otherwise, if it is bordering the the 1, the 4 is on top.

This question was raised and discussed in the forum of my companion site Wizard of Vegas.

This question was asked at TwoPlusTwo.com, and was answered correctly by BruceZ. The following solution is the same method as that of BruceZ, who deserves proper credit. It is a difficult answer, so pay attention.

First, consider the expected number of rolls to obtain a total of two. The probability of a two is 1/36, so it would take 36 rolls on average to get the first 2.

Next, consider the expected number of rolls to get both a two and three. We already know it will take 36 rolls, on average, to get the two. If the three is obtained while waiting for the two, then no additional rolls will be needed for the 3. However, if not, the dice will have to be rolled more to get the three.

The probability of a three is 1/18, so it would take on average 18 additional rolls to get the three, if the two came first. Given that there is 1 way to roll the two, and 2 ways to roll the three, the chances of the two being rolled first are 1/(1+2) = 1/3.

So, there is a 1/3 chance we'll need the extra 18 rolls to get the three. Thus, the expected number of rolls to get both a two and three are 36+(1/3)×18 = 42.

Next, consider how many more rolls you will need for a four as well. By the time you roll the two and three, if you didn't get a four yet, then you will have to roll the dice 12 more times, on average, to get one. This is because the probability of a four is 1/12.

What is the probability of getting the four before achieving the two and three? First, let's review a common rule of probability for when A and B are not mutually exclusive:

pr(A or B) = pr(A) + pr(B) - pr(A and B)

You subtract pr(A and B) because that contingency is double counted in pr(A) + pr(B). So,

pr(4 before 2 or 3) = pr(4 before 2) + pr(4 before 3) - pr(4 before 2 and 3) = (3/4)+(3/5)-(3/6) = 0.85.

The probability of not getting the four along the way to the two and three is 1.0 - 0.85 = 0.15. So, there is a 15% chance of needing the extra 12 rolls. Thus, the expected number of rolls to get a two, three, and four is 42 + 0.15*12 = 43.8.

Next, consider how many more rolls you will need for a five as well. By the time you roll the two to four, if you didn't get a five yet, then you will have to roll the dice 9 more times, on average, to get one, because the probability of a five is 4/36 = 1/9.

What is the probability of getting the five before achieving the two, three, or four? The general rule is:

pr (A or B or C) = pr(A) + pr(B) + pr(C) - pr(A and B) - pr(A and C) - pr(B and C) + pr(A and B and C)

So, pr(5 before 2 or 3 or 4) = pr(5 before 2)+pr(5 before 3)+pr(5 before 4)-pr(5 before 2 and 3)-pr(5 before 2 and 4)-pr(5 before 3 and 4)+pr(5 before 2, 3, and 4) = (4/5)+(4/6)+(4/7)-(4/7)-(4/8)-(4/9)+(4/10) = 83/90. The probability of not getting the four along the way to the two to four is 1 - 83/90 = 7/90. So, there is a 7.78% chance of needing the extra 7.2 rolls. Thus, the expected number of rolls to get a two, three, four, and five is 43.8 + (7/90)*9 = 44.5.

Continue with the same logic, for totals of six to twelve. The number of calculations required for finding the probability of getting the next number before it is needed as the last number roughly doubles each time. By the time you get to the twelve, you will have to do 1,023 calculations.

Here is the general rule for pr(A or B or C or ... or Z)

pr(A or B or C or ... or Z) =

pr(A) + pr(B) + ... + pr(Z)

- pr (A and B) - pr(A and C) - ... - pr(Y and Z) Subtract the probability of every combination of two events

+ pr (A and B and C) + pr(A and B and D) + ... + pr(X and Y and Z) Add the probability of every combination of three events

- pr (A and B and C and D) - pr(A and B and C and E) - ... - pr(W and X and Y and Z) Subtract the probability of every combination of four eventsThen keep repeating, remembering to add probability for odd number events and to subtract probabilities for an even number of events. This obviously gets tedious for large numbers of possible events, practically necessitating a spreadsheet or computer program.

The following table shows the the expected number for each step along the way. For example, 36 to get a two, 42 to get a two and three. The lower right cell shows the expected number of rolls to get all 11 totals is 61.217385.

Expected Number of Rolls Problem

| Highest Number Needed | Probability | Expected Rolls if Needed | Probability not Needed | Probability Needed | Expected Total Rolls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.027778 | 36.0 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 36.000000 |

| 3 | 0.055556 | 18.0 | 0.666667 | 0.333333 | 42.000000 |

| 4 | 0.083333 | 12.0 | 0.850000 | 0.150000 | 43.800000 |

| 5 | 0.111111 | 9.0 | 0.922222 | 0.077778 | 44.500000 |

| 6 | 0.138889 | 7.2 | 0.956044 | 0.043956 | 44.816484 |

| 7 | 0.166667 | 6.0 | 0.973646 | 0.026354 | 44.974607 |

| 8 | 0.138889 | 7.2 | 0.962994 | 0.037006 | 45.241049 |

| 9 | 0.111111 | 9.0 | 0.944827 | 0.055173 | 45.737607 |

| 10 | 0.083333 | 12.0 | 0.911570 | 0.088430 | 46.798765 |

| 11 | 0.055556 | 18.0 | 0.843824 | 0.156176 | 49.609939 |

| 12 | 0.027778 | 36.0 | 0.677571 | 0.322429 | 61.217385 |

This question was raised and discussed in the forum of my companion site Wizard of Vegas.

The Wizard says that website sounds like a lot of ranting and raving with no credible evidence whatsoever to justify the accusation. I'd be happy to expose any casino for using biased dice, if I had any evidence of it.

If anybody has legitimate evidence of biased dice, I'd be happy to examine it and publish my conclusions. Evidence I would like to see are either log files of rolls or, better yet, some actual alleged biased dice.

Furthermore, if the casinos really were using dice that produced more than the expected number of sevens, then why aren't these detectives privy to the conspiracy out there betting the don't pass and laying the odds?

- 2 or 12: 1,000

- 3 or 11: 600

- 4 or 10: 400

- 5 or 9: 300

- 6 or 8: 200

My question is what is average bonus win?

Craps Dice Roll Probability Rule

Click the following button for the answer.

Click the following button for the solution.

Let x be the answer. As long as the player doesn't roll a seven he can always expect future wins to be x, in addition to all previous wins. In other words, there is a memory-less property to throwing dice in that no matter how many rolls you have already thrown you are no closer to a seven than you were when you started.I won't go into the basics of dice probabilities but just say the probability of each total is as follows:

- 2: 1/36

- 3: 2/36

- 4: 3/36

- 5: 4/36

- 6: 5/36

- 7: 6/36

- 8: 5/36

- 9: 4/36

- 10: 3/36

- 11: 2/36

- 12: 1/36

Before considering the consolation prize, the value of x can be expressed as:

x = (1/36)*(1000 + x) + (2/36)*(600 + x) + (3/36)*(400 + x) + (4/36)*(300 + x) + (5/36)*(200 + x) + (5/36)*(200 + x) + (4/36)*(300 + x) + (3/36)*(400 + x) + (2/36)*(600 + x) + (1/36)*(1000 + x)Craps Dice Roll Probability Dice

Next, multiply both sides by 36:

36x = (1000 + x) + 2*(600 + x) + 3*(400 + x) + 4*(300 + x) + 5*(200 + x) + 5*(200 + x) + 4*(300 + x) + 3*(400 + x) + 2*(600 + x) + (1000 + x)36x = 11,200 + 30x

6x = 11,200

x = 11,200/6 = 1866.67.

Next, the value of the consolation prize is 700*(6/36) = 116.67.

Thus, the average win of the bonus is 1866.67 + 116.67 = 1983.33.